Six cognitive biases that affect your leadership

Cognitive bias affects us all. Regardless of how rational or objective we believe ourselves to be, we are still prone to making mistakes in reasoning, evaluating, recollection and other cognitive processes. These mistakes usually occur as a result of holding onto our preferences and beliefs regardless of contrary information.

It’s important to understand that we can’t avoid cognitive bias – thinking that you can may be a sign of cognitive bias itself! Because it’s so often unconscious, merely telling ourselves to do better won’t solve the problem. Having systems that can be put in place to reduce the impact of cognitive biases in play is an important part of improving your critical thinking skills.

Watch out for these six cognitive biases

Although cognitive biases influence decisions all the time, as a leader, you need to be more aware of the outsized impacts that your decisions can make if they are influenced by bias. Fortunately the first step to overcoming, or at least mitigating, leadership bias is awareness.

Here are six of the primary leadership biases that can have an impact on how you lead your team and the decisions you make.

1. Affinity bias

Affinity bias relates to the predisposition we all have to favour people who remind us of ourselves.

When applied to regular workplace processes such as hiring and promoting, at its best, this bias sees successful people willing to give someone a chance because of their similarities. We’ve all heard or read the phrase, “You remind me of myself at that age,” and understand how that kinship can result in favorability. You may have also seen this type of cognitive bias in hiring in the form of the “beer test” – where employers prefer to hire someone if they could see themselves having a beer with them.

But demographic minorities are often disadvantaged when affinity bias is brought into hiring decisions. Without meaning to, a leader who is Caucasian and male will be more likely to hire people who remind him of himself. Even when men consider themselves egalitarian and have no stated prejudice against other groups, studies show that affinity bias occurs. That’s because it’s happening on a subconscious level, and the hirers are not conscious of why they’re making the decisions that they are.

Hiring practices that can help with this problem include “blind screening”, where the candidate’s application is stripped of personally identifying data. While that’s been proven to help, it only addresses the initial hire. Ensuring fairness for promotions, pay-rises and intangible opportunities to train or network is still harder to achieve.

2. Confirmation bias

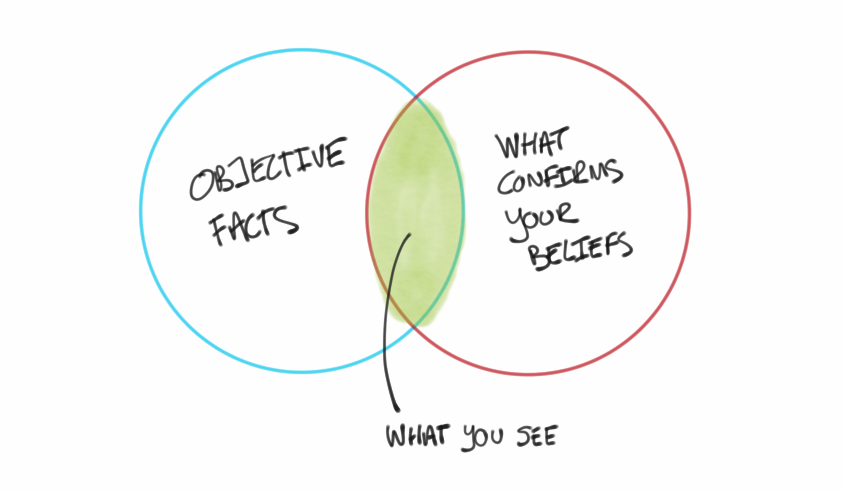

Confirmation bias is our human tendency to seek out or notice information that supports our existing beliefs. This cognitive bias can be a problem for leaders, who need to be open to feedback, solutions and ways of doing things that they may not have favoured in the past.

If you’ve already made up your mind that a certain path forward is the correct one, confirmation bias will lead you to place more value on evidence that supports your plan than any evidence that does not. You could disregard useful feedback, dismiss innovative ideas and solutions, which may ultimately lead to poor decision-making.

Fortunately there are ways to combat confirmation bias. When you’re about to make a decision, look for ways to challenge what you think you see. Seek out information from a range of sources and discuss your thoughts with a diverse group of people. Then, share the feedback you get with a wider group again for greater discussion. For major decisions, even consider assigning someone on your team to play devil’s advocate.

Source: Farnam Street

3. Conservatism bias

Similar to affinity and confirmation bias, conservatism bias sees us favour familiarity. In this case, it’s favouring existing information over new information that threatens to change our preconceptions. When we do get new information, we tend to value it less or dismiss it, while information that supports a previous belief is given more weight.

While it seems laughable to us now that it was once widely believed that the earth was flat, convincing people otherwise was a slow and hard-won battle.

For leaders, conservatism bias can make change management particularly challenging. Even where there are compelling reasons to change a business system, introduce new processes or modify roles, people are likely to cling to the old way of doing things. They’re not just being stubborn – they literally aren’t seeing the new information as important. As a leader, understanding this trait will make guiding your people through change easier on everybody.

4. Fundamental attribution error

Fundamental attribution error is a type of cognitive bias that refers to our tendency to believe that what people do reflects who they are. This bias sees us overemphasise personal characteristics and ignore situational factors when judging others’ behaviour.

As leaders, the tendency to assume that someone’s behaviour is a part of them and unchangeable is extremely limiting. It prevents us from being able to look at their external situation and make changes that can improve those behaviours.

A habitually late employee could be lazy and unmotivated, or they could have caring responsibility at home. In the latter case, the ability to start later in the day or work from home when needed could see their productivity soar.

If you’re inclined to blame your staff for something you perceive as a character flaw, take a step back. Ask yourself what other possible explanations there might be for their behaviour, and then approach the solution in good faith.

5. Recency bias

Recency bias is an unconscious tendency to consider events that happened recently, or information received recently, to be more important than those that were less recent.

This cognitive bias was discovered by researchers who realised subjects who were asked to memorise lists had the most success recalling whichever items were last on the list. But once you’re aware of recency bias, it’s not difficult to see it at play in professional settings.

Recency bias may manifest as giving more weight to recent data over long-term trends, or – arguably in its worst form for leaders – as a likelihood to be influenced by the views of the people they spoke with most recently. We’ve all encountered leaders like this, and the bias can greatly diminish their effectiveness.

The opposite of recency bias – favouring whatever happened first – is known as primacy bias, and can impact decision-making in very similar ways.

6. Proximity bias

Proximity bias is another type of cognitive bias that leads people to place more value on things that are familiar. In the case of proximity bias specifically, it means that we are more likely to favour things – and people – that are closer to us, or that we see more often.

For managers and leaders, the main risk is that this bias can manifest as favouritism towards employees they see more often. This can have insidious effects in any workplace, but it is especially important that hybrid or distributed workplaces – those where some team members work remotely some or all of the time – can mitigate against this cognitive bias.

Leaders need to be aware of this bias to ensure that they are not overlooking or placing at a disadvantage members of the team who are not always in the office with them.

Noticing cognitive bias is the first step

The thing that makes cognitive bias such a risk for leaders is their naturally stealthy nature. It takes both self-awareness and vigilance to be able to recognise when cognitive bias is impacting your leadership and decision-making. There are many pathways to becoming a stronger leader, such as earning an MBA or finding a mentor, but developing the ability to notice leadership biases should be part of any aspiring leader’s plans.

Have you noticed any cognitive biases at play in your industry? As a leader, how do you ensure you’re as fair as possible?

This article was written by Tanya Ashworth-Keppel on behalf of the Australian Institute of Business and revised July 2021. All opinions are that of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of AIB. The following sources were used to compile this article: The Guardian, Business Insider, New York Times, Monash University, The Conversation and Harvard Business School.

Image credit: Essentia Analytica